Many years ago, when I was learning about databases, the mantra was normalize, normalize, normalize. We were taught to build schemas in Third Normal Form (3NF) — break the data into smaller tables, eliminate redundancy, and ensure consistency. At the time, it made perfect sense.

Why? Two main reasons:

- Storage was expensive. You didn’t want redundant data lying around.

- Desynchronization was dangerous. If you duplicated data, you risked inconsistency across the system.

Both of these concerns shaped how we designed systems.

Fast forward to today. We are building microservices, not monoliths. And here’s the thing: 3NF thinking is counterproductive in this world.

The Core Principle: Data Locality

A microservice should already have all the data it needs to do its job.

That sounds obvious, but many designs still fall into the trap of treating microservices like normalized tables — keeping them small and “lean” and expecting to fetch missing data from other services on demand.

Here’s the question I like to ask:

👉 How many invocations should a microservice make to other microservices to fulfill its responsibility?

The answer is: 0.

Why? Because if every microservice assumes “just one call won’t hurt,” you quickly end up with chains of invocations across your system. That single request balloons into a massive call graph — slow, fragile, and almost impossible to debug in production.

But What About Storage and Consistency?

Let’s revisit the two old 3NF arguments.

- Storage cost?

It’s no longer a constraint. For example, on AWS RDS today, 10 GB of storage costs just a few cents per month. That’s pocket change compared to the engineering time wasted chasing performance problems caused by poor data locality. - Desynchronization risk?

Distributed systems are inherently eventually consistent. That’s not a bug — it’s a feature. Instead of fearing it, we embrace it and design with it in mind.

We also have tools to mitigate issues:

- Outbox pattern ensures reliable event propagation.

- On the producer side: at-least-once delivery.

- On the consumer side: at-most-once delivery.

This means we can safely replicate data across services without introducing chaos.

A Concrete Example: Authentication & Authorization

Let’s take a simple case. Suppose we are building an identity system with three business processes:

- Registration

- Authentication

- Authorization

For simplicity, I will show you how this can be achieved both in the single deployable unit and microservices architecture.

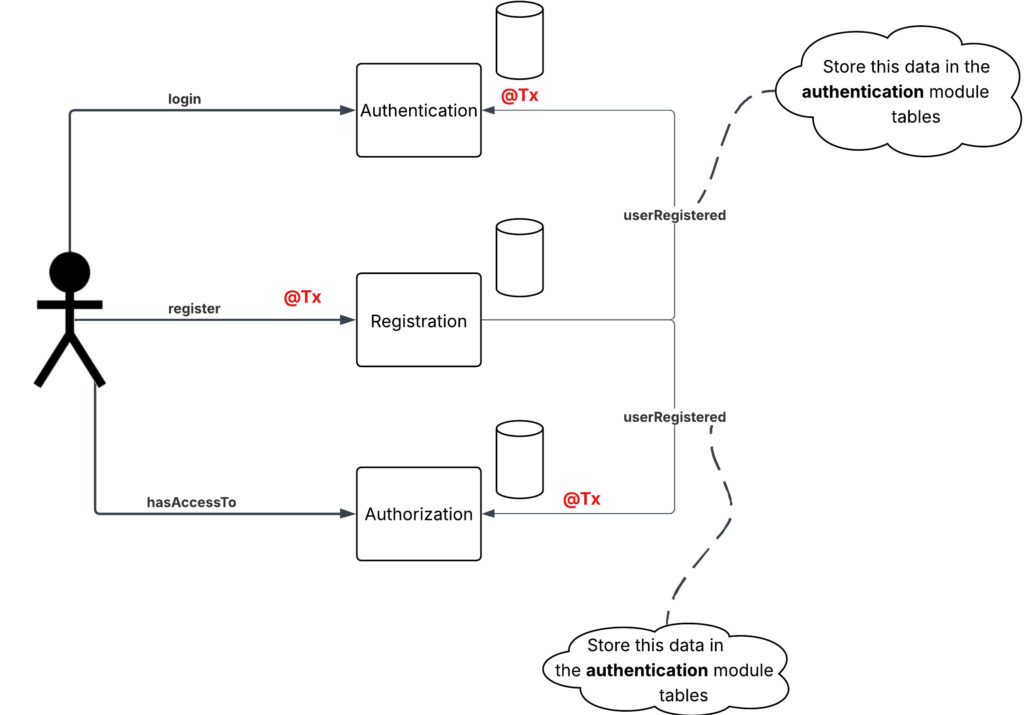

Inside a deployable unit (e.g., single JVM)

- Each module has its own set of tables inside the same database instance.

- When a user registers, we save data into Registration, Authentication, and Authorization tables in a single transaction.

- Data locality is preserved. No calls between application modules needed. If the process inside Authorization changes, registration and authentication modules are untouched. This allows to decouple your functionality based on the processes, not nouns like “user” or “customer” which contain all fields describing the entity, which are not necessarily needed in all processes (e.g., authorization does not need login or password of a certain user, it needs his roles!)

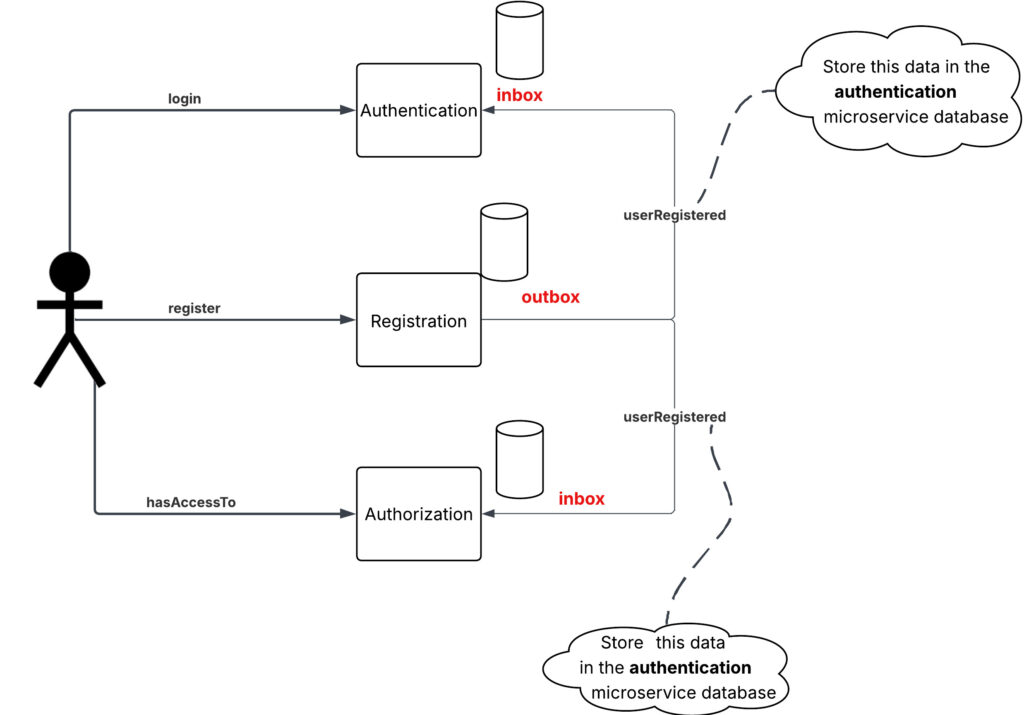

In a Microservices Architecture

- Each service has its own database.

- When a registration happens:

- The Registration Service saves its data.

- It emits an event into an outbox table.

- The event is published to Kafka (or another broker).

- Authentication Service and Authorization Service consume the event and update their own stores.

Now, each microservice has the data it needs. No service depends on runtime invocations to fulfill its core responsibility.

Closing Thoughts

Microservices are not distributed 3NF tables. They are autonomous units of responsibility. To keep them fast, reliable, and scalable, they need local ownership of data.

Storage is cheap. Eventual consistency is a design choice, not a flaw. Outbox patterns and event propagation solve synchronization issues.

So next time you’re designing a microservice, ask yourself:

- Does this service have all the data it needs to do its job?

- Or is it relying on calls to others?

If the answer is the latter, you’re setting yourself up for a fragile system.

Microservices should call other services for collaboration — not for their core responsibility.